‘This female artist gifted with masculine qualities’. About mapping forgotten female artists

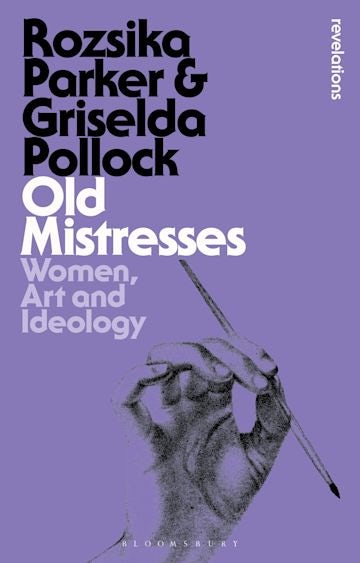

Since the 1970s, the fact that female artists are underrepresented in art history has been brought to the attention. Feminist thinkers, art critics and historians such as Griselda Pollock, Rozsika Parker and Linda Nochlin sound familiar to us all, but has their cry for change really paid off? It is important to note that their ideas were widely followed, but feminism that was too outspoken often had a counterproductive effect on public opinion. Today, some 40 to 50 years later, female artists still remain very invisible, they form only a small part of museum collections, and the economic value of their work is much lower than that of their male colleagues. This still very topical issue has been repeatedly brought to the attention in recent years, in the form of lectures, essays, books and exhibitions with accompanying catalogues.

Recently for example, on 8 March 2023 – International Women’s Day – a conference titled ‘Does sex matter?’, organised by FARO, took place in the Yper Museum. The panel discussions between professionals from the field provided relevant views and were an inspiration for my own deep-rooted interest in researching forgotten female artists. The women that is, who, unlike their male colleagues, often disappeared between the folds of art history. Since the Master of Art History (KULeuven) gives us relatively much freedom to shape our curriculum according to our own interests and passions, I chose to focus on this discrepancy in the arts – during both my internship and my thesis research. With a view to innovative insights that could bring us, art historians, one step closer to the inclusiveness of women, I set to work.

Anke Vermeulen (KULeuven) tijdens haar stage bij CKV.

The canon

My personal vision puts equality thinking above difference thinking. I try to view artists as one mutually influencing group in which every relevant artist deserves a place, regardless of gender. In this line of reasoning, the woman’s artistic qualities are equated with those of her male contemporaries, so that they are ideally exhibited together. In a sense, female group exhibitions that are based solely on the fact that the artists shown are ‘women’ confirm and emphasise the inequality. Our Western canon also contributes to consolidating the problem. This is due to its reductive and strongly restrictive nature, making it seem legitimate to leave all kinds of artists in oblivion. The canon tries to paint a representative picture of artists who are considered leading for a certain period, but it hardly includes any women – which is not in line with reality.

Various thinkers have repeatedly written about and discussed the canon, also within art history. French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2000) for example, argued that the canon is not only a reflection of the art world, but also of society and the political and economic power relations that play a role in it. He saw the canon as an instrument of cultural power and believed that its selection of works and artists was determined by an elite of art critics and curators. In this way, the canon functions as a kind of ‘cultural capital’ that people can use to strengthen their position in society. However, Bourdieu was not against the instrument itself, but against the way in which it is created and used. He therefore argued for more inclusion and diversity and for recognition of works and artists that fall outside the canon, but are nevertheless very valuable. The canon should therefore not be a static element, but must always be revised and further developed.

The research

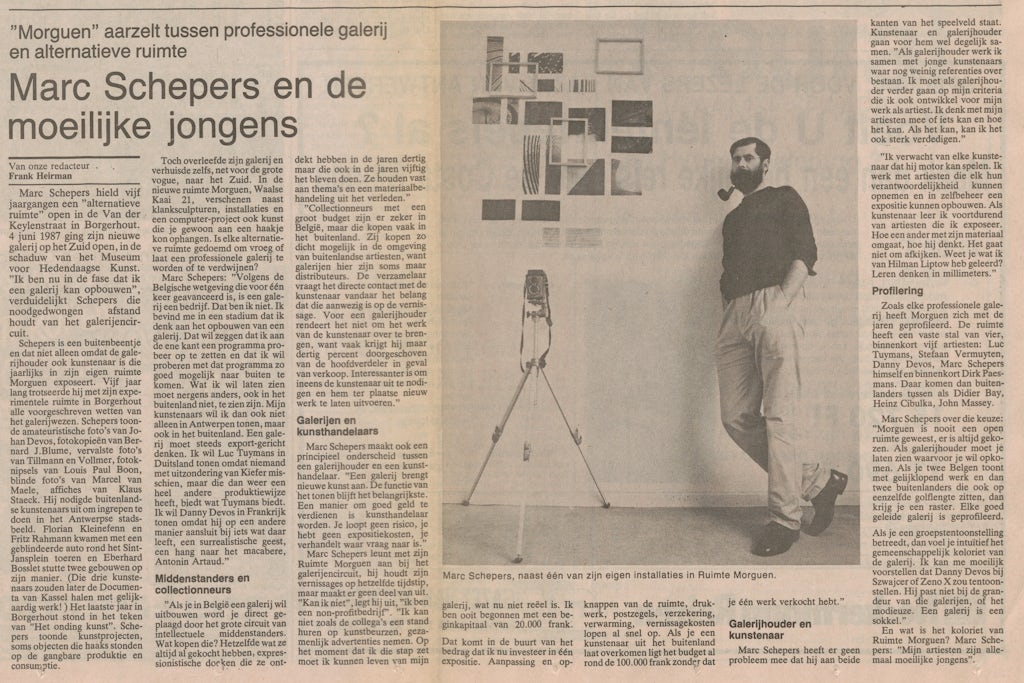

Having said that, I will come back to the research itself in a bit more concrete terms. It was of course impossible to highlight the gigantic group of ‘systematically forgotten female artists’ in one academic year: making a selection was difficult, because choosing is always losing. Fortunately, I still have a whole life ahead of me as an art-loving researcher, so I view this research as a starting point that can go in any given direction. As part of my thesis, I decided to work on Ghent artist Irène Hamerlinck (1903-1995). At first I wanted to take a closer look at the artist, her career and her oeuvre. The second part of my research focuses on the way in which people wrote about the artist and her work in contemporary media. Source material was very fragmentary and took me from the Antwerp Letterenhuis, to the Brussels Archives et Musée de la Littérature, the MSK in Ghent, the Antwerp KMSKA, the Hamerlinck family in Ghent and Deurle, and so on.

Today, Hamerlinck is described in marketing terms by auction houses as ‘the artist who was portrayed by Jean Brusselmans’. The oeuvre of artists is always coloured by various factors: their teacher(s), the journeys they undertake, the entourage in which they are active, the society in which they live, the trend that prevails at the time etc. The share of a female artist herself within her artistic development is often underexposed. On the one hand, they are often placed in ‘the shadow of their master’, while they deserve more credit for the work they have realised with their own hands. On the other hand, these women themselves sometimes strategically capitalised on the training they received from a particular master to indicate that they were not amateurs. Because in the 19th and 20th centuries, women were often associated with dilettantism and amateurism, even when they were professionally active as artists.

Research also shows that Irène Hamerlinck exhibited with Paul Delvaux, Jean Milo, René Magritte, Suzanne Van Damme, Rachel Baes, Gustave De Smet, Fritz Van den Berghe, Victor Servranckx and others. She belonged to the entourage of E.L.T. Mesens and was part of his Belgian selection at the Congress of British Artists in London. Today, many of her colleagues’s paintings feature in well-known museums, enjoying global fame. During her active period, Hamerlinck was also greatly appreciated by contemporaries, colleagues and critics. With each new source, my enthusiasm grow, and I kept asking myself: ‘How is it possible that almost nobody knows her?’

In my search concerning Hamerlinck’s artistic life, I came across dozens of other women: a whole network of female artists about whom I rarely or never heard. Who today still knows Alice Keelhoff (1896-1983), Suzanne Bomhals (1902-2000) or Marie De Keyser (1899-1971)? From the word go, the urge to take further steps in this field of research was strong. Numerous new findings made me want to expand the research further.

The importance of an inclusive service

During my internship at the Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen (CKV), I was given the opportunity to continue with this. At first I tried to draw up a field map of female artists who were active in the Ghent art landscape between approximately 1945 and 1995. In a relatively short period of time, this list expanded greatly: more than 100 names surfaced.

The CKV supports artists, galleries, art critics, art organisations and other actors from the field of the visual arts in their care for their archives. In the context of this internship, it was therefore relevant to continue working with this field map and, on the basis of genealogical research, to trace next of kin who may have provided an archive. Within this part of the research process, archiving, collection management and collection preservation and the engagement of the next of kin play a key role. All relevant information collected after the death of artists makes reconstruction much easier.

In the case of female artists, this often causes problems. First, they did not always have a husband, and if they did, they often survived them. Many a professional female artist also remained childless: if she did choose children, her artist career often had to make way for the family. When she did leave behind a husband or children, the latter were not always aware of the importance of archiving – in the context of her survival in the arts. The conference ‘Does sex matter?’ showed that women attach more importance to archiving for the benefit of their husbands. Practice shows us that this will be much less the case when it are the men doing the archival work for their spouses.

Starting from my art history training, I added an extra dimension to this research. Here too, just like in Irène Hamerlinck’s case, I wanted to see how people wrote about the women in question in contemporary press and media. In Old Mistresses (1981), Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker investigated the ways in which the artistic production of women is misunderstood and undervalued in art history. They examined which adjectives were used for a spectrum of artists. The men were called virile, strong, brave, daring and ambitious. In stark contrast to these notions, women were mainly described as sentimental, decorative, searching and feminine.

To a certain extent, this also applies to my research into 20th century Ghent. Striking are the many comparisons between men and women, with the man being ‘the good example’. Statements along the lines of ‘this female artist gifted with masculine qualities’ were no exception. Women were said to be sensitive, weak and hysterical and thus stood in contrast to their male colleagues. They were literally described as the opposites of men, simply not having the same capabilities and qualities to go far in the arts.

We can say that some initiatives have been taken in recent decades in the context of the issues discussed here. Still, we definitely didn’t reach our goal yet. How come? First of all, studies like the present one are very time consuming, and time costs money and resources. In addition, it is not easy to bring together all the fragmentary information into a homogeneous story. Many works are in private collections or are sleeping in depots, contemporary sources are rarely located at one central point, and it is often difficult to filter relevant source material from databases. However, it is worth highlighting forgotten artists and continuing to work on this subject.

It is therefore very important that a heritage organisation such as CKV – despite the limited capacity at its disposal – is committed to its service mission for all actors, including these forgotten female artists. Finally, within this twofold study I hope to enthuse and inspire other academics to step outside the standard conventions and the ‘familiar’ canon.

AV